From Nigel Savage

There’s a fascinating academic study on the aftermath of the Brexit vote in the UK. One of the things it looked at was the relationship between social capital and the referendum. It defines social capital as the resource that arises from interpersonal networks and the norms of trust and reciprocity that facilitate social interaction within them – the ‘glue’ which helps society function. Those with high social capital can draw on the people they know – family, friends, and community – for support in all aspects of life. High social capital has been linked with positive outcomes in a range of areas, from better government, higher levels of health and education, lower levels of crime, and even less tax evasion. People with high social capital may be better able to adapt to changes in their personal situation and changes in their communities because they are able to draw on more extensive social networks.

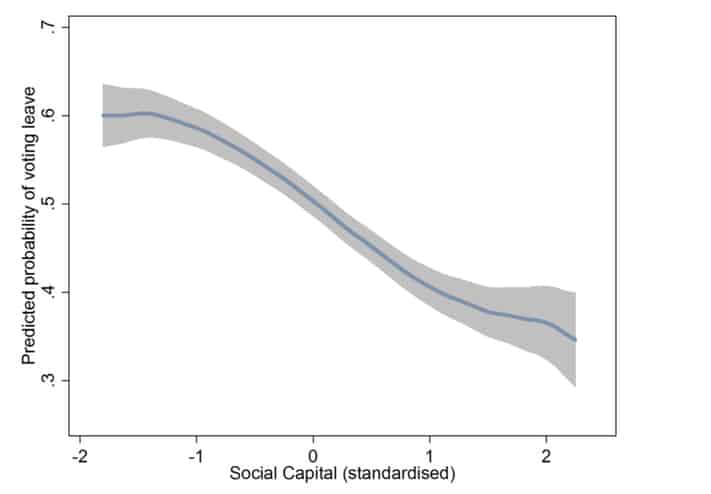

The study showed a strong trend between social capital and Leave voting – those with the lowest levels of social capital were almost twice as likely to have voted Leave [on Brexit] as those with the highest levels.

That’s a remarkable finding. And my strong instinct is that the US presidential election will show a similar correlation.

If this is the case, there are complex implications for all of us.

At one level, there is our response as individuals. We’re increasingly influenced by the wellness pages of newspapers and magazines. If you’re trying to walk more, or eat fewer carbs or more green vegetables, if you’ve tried to develop a meditation practice: each of these things, and many more, comes to us via research that shows them to be good for us. The notion that social capital is good for us – and that social isolation causes negative health outcomes for us as individuals – is in and of itself an argument for us to develop stronger cultures of community. This is both prescriptive (what we should be doing) and also descriptive (why certain things are happening).

I’m convinced, for instance, that the strength of Modern Orthodox shuls in many parts of the country is far more sociologically than theologically rooted. A suburban Reform or Conservative temple may have met some of the psychic needs of American Jews in the 1950s and ’60s, but we have different needs today – and many of those suburban institutions are failing to meet them, often through no fault of their rabbis or leaders. Our needs have simply changed. It is less important to us to have a synagogue that matches in style and architecture that of our Protestant neighbors. It is far more important – in our hyper-mobile society – to have structures that engender deeper ways of connecting to each other.

So as individuals we should seek out community. We should commit to it. We should join shuls, host meals, attend shivas, reach out to people, make clear that we’re willing to have others reach out to us. If you’re part of a community that enables you to do this, dive in. If you really feel your shul isn’t conducive, then find another one. Don’t allow your own shyness to hold you back. Jewish life, like all traditional communities, encourages a web of social commitment that is subtle but profound. Be brave. Take the first step. Make the first call. Nothing bad will happen.

And if you’re the leader of a shul – especially a non-Orthodox one, of any flavor – I think it vital to throw open the doors of the institution on Shabbat, invite people to come, whether they come to services or not, and find ways to help people to connect. Host a book club. Start a choir. Learn Talmud. Have a yoga class. And host meals on a far more regular basis. Shuls need to have proper kiddush meals, as frequently as possible, and they also need to find ways to encourage people to attend and to host Shabbat meals in each others’ homes. That has been the heart of Jewish life for twenty centuries. Shuls that don’t enable and encourage us to eat together aren’t doing their job properly – no matter what else they are doing.

But then, beyond this, there is the wider communal response. What do we need to do as a wider society, as a community, as a country? We have, or should have, safety nets for those whose absence of financial capital leaves them exposed to illness or old age. But what are the safety nets for communities or individuals whose absence of social capital leaves them similarly isolated or exposed?

This is not a rhetorical question. I don’t know the answer. But it is clear that the diminution of social capital shows up not just in suicide rates or obesity statistics; we’re seeing it now also in the political realm. The UK study makes plain a direct correlation between, for instance, low social capital and hostility to foreigners.

From a Hazon perspective, I note that people asked me, a few years ago, why on earth we were working on “intentional communities.” What was an intentional community – and wasn’t Hazon about bikes and food?

But Hazon wasn’t about bikes and food. Elat Chayyim wasn’t about meditation. Adamah isn’t about farming. Teva isn’t about “the environment.” Each of these things is partially and proximately true, of course, but they genuinely miss a wider and deeper intent. I’m on my way to Israel for our Israel Ride. But our Israel Ride isn’t about bikes, either. Howie Rodenstein, who co-founded it, loves riding his bike; but that’s not why he founded the Ride.

Our larger commitments define who we are, provide meaning for our lives, and help us to strive to be better people. Hazon’s work on intentional communities – like our retreats and rides, like our curricula resources, like the Hazon Seal, like Adamah and Teva – are rooted in a genuine commitment to health and sustainability. How do we help the Jewish community to be healthier and more sustainable? How do we help create a healthier and more sustainable world for all?

There is no one answer. We each have a role to play. And this year’s elections remind us that a challenge we may think of as individual or communal is also societal and national. (One of the reasons we’re trying to do proportionately fewer open retreats at Isabella Freedman and more institutional retreats is that institutional retreats afford a far greater opportunity to thicken community, ie to strengthen social capital within a particular institution.)

Finally, therefore, and in no particular order:

1. You’re warmly invited to our Jewish Intentional Communities Conference from December 1-4 at Isabella Freedman. Headliners include Cheryl Cook, Liz Fisher, James Grant-Rosenhead, and Aharon Ariel Lavi, looking at the cutting edge of community in contemporary Jewish life. Plus davening options led by Rabbi Avram Mlotek (Orthodox), Rabbi Jessica Kate Meyer (Renewal) and Avi Garelick (Traditional Egalitarian).

2. And to our Meditation Retreat, taking place at Isabella Freedman from December 18-25. It’s led this year by Rabbi Jay Michaelson, Beth Resnick-Folk, Rabbi Naomi Mara Hyman, and Shir Yaakov Feit.

3. And our Food Conference, over Shabbat Hanukkah and New Year’s Eve at Isabella Freedman. Amazing food, amazing people, great sessions – it will sell out, so if you want to come you should book now.

4. If you want to bring your community to do a retreat at Isabella Freedman in ’17 or ’18 (or you want to join us for your simcha) speak to Eli Massel, eli.massel@hazon.org.

5. And don’t forget to vote.

PS – for those who are interested – the graph below illustrates the relationship between social capital as measured by the resource generator and the likelihood of voting Leave estimated by a nonparametric local polynomial regression. It shows a strong trend between social capital and Leave voting – those with the lowest levels of social capital are almost twice as likely to have voted Leave as those with the highest levels.

Comments are closed.